The Institute on Metropolitan Opportunity is pleased to feature the School Desegregation News Roundup: periodic updates and reflections on educational desegregation and related issues, provided by Peter Piazza, an education policy researcher at Penn State's Center for Education and Civil Rights. Updates are crossposted on his site, available here.

In case you missed it, this administration continued its effort to rollback of civil rights protections for K-12 students in its reversal of Obama-era guidance on school discipline. Specifically, the “school safety” commission convened after the Parkland shooting issued a report calling for a repeal of the Obama Administration’s 2014 guidance on school discipline. The report – signed by Betsy DeVos, Kirstjen Nielson and Matthew Whitaker – was released earlier this week (full text here). A few days later, the administration officially revised the Obama-era school discipline guidelines to align with the recommendations in the school safety report.

In case you missed it, this administration continued its effort to rollback of civil rights protections for K-12 students in its reversal of Obama-era guidance on school discipline. Specifically, the “school safety” commission convened after the Parkland shooting issued a report calling for a repeal of the Obama Administration’s 2014 guidance on school discipline. The report – signed by Betsy DeVos, Kirstjen Nielson and Matthew Whitaker – was released earlier this week (full text here). A few days later, the administration officially revised the Obama-era school discipline guidelines to align with the recommendations in the school safety report.

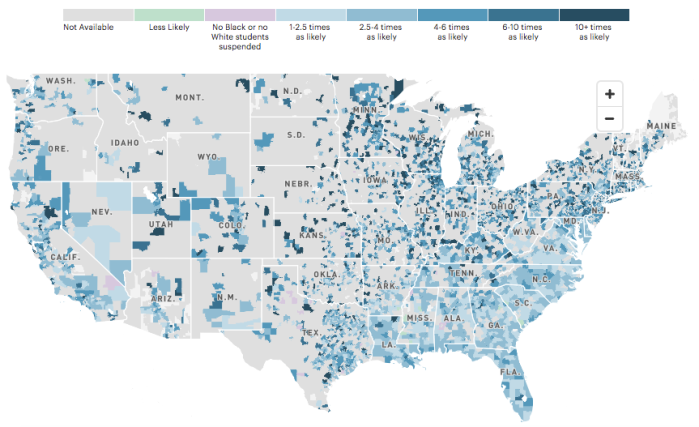

Before talking about the guidance, I want to go to this map from ProPublica’s Miseducation website. I have just a screenshot here, but if you follow the link you can get to the interactive version. Under “measure” you can select “discipline” and then you can see a nationwide map of school districts where Black students are more likely to be suspended than White students. If you have a few minutes, try to find one district where this is “less likely.” (The numbers will pop up when you hover over each district.) I’ve spent a decent amount of time with this, and I still haven’t found a single district, in the entire country. As I’ve written previously, research points clearly to the harmful and racially disproportionate effects of unconscious bias and exclusionary discipline, and this has real consequences for students, their families and all of us.

Nonetheless, the new administration guidance “[gets] rid of Obama administration guidance aimed at making sure students of color and students with disabilities aren’t disciplined more harshly than their peers,” as written in this Ed Week summary. A few quick points:

- As described in the New York Times, “The 2014 Obama policy advised schools on how to dole out discipline in a nondiscriminatory manner and examine education data to look for racial disparities that could flag a federal civil rights violation.”

- Here are a few lines from the Obama guidance:

- Disparities in discipline rates could not be explained solely “by more frequent or more serious misbehavior by students of color.”

- “In short, racial discrimination in school discipline is a real problem”

- That’s been replaced with:

- “Research indicates that disparities that fall along racial lines may be due to societal factors other than race”

- The Obama administration “gave schools a perverse incentive to make discipline rates proportional to enrollment figures, regardless of the appropriateness of discipline for any specific instance of misconduct.” In short, schools may have been right to discipline Black students more harshly than White students. This is what white supremacy looks like in policy.

Because this blog focuses on race and civil rights, I haven’t discussed the report’s recommendations on gun violence in schools. But that part is also quite upsetting. Here are just a few key points from an additional Ed Week summary:

- The report strongly encourages states to place more armed personnel in school.

- Along those lines, it recommends that districts make it easier for military veterans and retired law enforcement officials “to become certified teachers,” so that they can carry guns and use them if necessary.

- It does NOT recommend age restrictions on firearms purchases.

The New York Times also has a great story about how the report plays down the role of guns in its decision to instead focus on discipline. And there’s a very strange connection between the two topics. Specifically, the report justifies its proposed repeal of the Obama guidance by essentially saying that its approach to discipline was too soft. Again, this entire report was commissioned in response to Parkland. The implication is that the Obama guidance had something to do with the Parkland shooting and/or repealing it will somehow prevent more school shootings.

Before committing the Parkland massacre, Nikolas Cruz was referred to an alternative discipline program for nonviolent offenses, called the PROMISE program. The report argues that “some alternative discipline policies encouraged by the [Obama] Guidance contributed to incidents of school violence,” as part of its justification for repealing the prior guidance. However, pointed out across several articles:

- Cruz had been “expelled from school, banned from campus, and had been referred to law enforcement numerous times.” So he’d also been the subject of the harsher forms of discipline favored by the current administration.

- The PROMISE program was established in 2013, before the Obama discipline guidance had been released.

- It’s not clear if Cruz even attended the program.

- And, from Ed Week: “A state panel created to investigate the shooting said in July that the PROMISE program had “no bearing on the outcome” and did not affect the gunman’s ability to purchase firearms, as some had speculated.”

In other words, any connection between Parkland and school discipline reform is completely invented.

For those who wanted to dive into this in more detail, I wanted to briefly highlight a couple key issues. The articles linked here are great resources for those who want to learn more. In particular, I use an article from Dan Losen, Director of the Center for Civil Rights Remedies at the UCLA Civil Rights Project, to respond to the following common criticisms of the Obama guidance:

- Disparate Impact and Quotas – A key element of the Obama guidance was the notion of “disparate impact,” or that schools could be in violation of civil rights law if discipline efforts have disparate impact regardless whether there was any discriminatory intent. Critics of the Obama guidance have claimed that this led school administrators to implement quotas for exclusionary discipline – e.g., making sure that exclusionary discipline was racially balanced. From Dan Losen’s article:

- “No districts have been found to have adopted disciplinary racial quotas in response to the guidance.” If districts on a large scale had been using quotas, then one would expect suspension rates to decline. Instead, “national school-discipline data from 2013-14 show a slight decline in suspension rates when compared to 2011-12, but the rates today are far higher than they were in the 1970s and 1980s.” In addition, for the “quota” argument to have merit, critics would have to demonstrate that the recent and slight decline has made schools less safe (again – this is the central argument of the recent school safety report). Instead, Dan Losen notes that “there is no evidence that a slight decline of a percentage point or two has caused safety problems.”

- Government overreach – The Obama guidance was developed as a response to the national trends seen above in the ProPublica map, and therefore encouraged districts to pursue certain types of discipline (e.g., restorative approaches) over other types (especially exclusionary discipline). For this reason, critics cite the Obama guidance as federal government overreach, in dictating how to discipline students from the highest levels of government. Again, Dan Losen’s article is a reminder that:

- “The core question for disparate impact is whether the policy is justifiable in light of its harmful impact.” The Obama guidance isn’t telling schools that they can’t suspend students; instead, it is encouraging schools to make sure that exclusionary discipline is justifiable. There’s even a flow chart in the Obama guidance to help schools/districts figure out if a suspension decision is “educationally sound and justifiable,” which is especially relevant for cases like tardiness or other non-violent offenses. As Dan Losen notes, the decision to suspend should be balanced against “its harmful impact,” or, in other words – the overwhelming research that links exclusionary discipline to negative future outcomes. For example, he notes that one study followed students for 12 years and found that “students who were suspended were less likely to have graduated from high school or college and more likely to have been arrested or on probation.”

Of course, there’s a lot more to say about each topic. While it’s important to debate these aspects of the new report and guidelines, I don’t want to get lost in the details. I do worry that picking a part individual arguments gives the report more legitimacy than it deserves. In the end, for me, it’s the bigger picture that matters the most here. And, that bigger picture is particularly troubling, even for this administration. Specifically: I don’t want to lose track of the fact that the new guidance uses a national tragedy to justify removing civil rights protections for Black and Latinx students. Or that it leans heavily on harmful stereotypes about Black and Latinx students by strongly implying that racially disproportionate discipline is necessary to keep schools safe. As described this statement from the Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights:

“It is unconscionable to use the very real horror of the shooting at Parkland to advance a preexisting agenda that encourages the criminalization of children and undermines their civil rights.”Vanita Gupta, President of the Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights

It it further troubles me that the administration likely knew what they were doing and tried to bury it by releasing the new guidance on the Friday before Christmas.