The Institute on Metropolitan Opportunity has conducted new analysis of national school enrollment data from 2014-2015. This analysis supports the conclusions of the AP report. It suggests that students in charter schools are more likely to be sorted by race than students at traditional schools.

The analysis compares the racial enrollment demographics of charter and traditional schools to the demographics of resident students in the municipalities in which the schools are located. The data, obtained from NCES, includes virtually all American public schools, with the exception of a small number of schools for which demographic figures are unavailable.

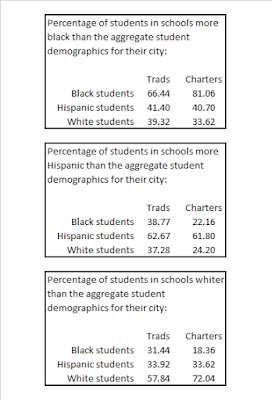

Key findings include:

- 81 percent of black students in charter schools attend a school that is more black than the overall student population of their city, compared to 66.4 percent of black students in traditional schools.

- 72 percent of white students in charter schools attend a school that is whiter than the overall student population of their city, compared to 57.8 percent of white students in traditional schools.

- Compared with traditional schools, a substantially smaller percentage of black and white students in charter schools attend a school with a higher share of Hispanic students than the overall student population of their city.

In short, charter enrollment shows clear signs of racial "sorting," in which students attend schools that are disproportionately composed of their own racial group. A table with full findings is included at the bottom of this post.

The following graph, depicting almost every American charter school, helps illustrate the basic nature of charter sorting. Each point is a single school. The horizontal axis represents the white percentage of the overall public school enrollment of the school's municipality; the vertical axis is the white percentage of the school's own enrollment. Bubbles are scaled to the absolute number of white students enrolled in a school. (Click the graph to enlarge.)

As can be seen, the vast majority of white students are enrolled in charters that are whiter than the overall enrollment in their city. Moreover, most white students enrolled in a more diverse school are already located in a very white city.

The next graph depicts the same data, but instead scales the bubbles to overall nonwhite student enrollment. Once again, it is clear that a large share of nonwhite students are enrolled in a school that is more segregated than their city's overall enrollment (i.e., below the diagonal). Indeed, the pattern is stronger than it may initially appear, as a huge number of overlapping schools are concentrated in the bottom left quadrant of the graph.

In order to better highlight this concentration, a third graph uses the same data, but removes the scaled bubbles for clarity. In this graph, an orange box contains all charter schools that are both less white than the surrounding city's overall enrollment, and more than 90 percent nonwhite (or, the parlance of our earlier reports on charter segregation, "hypersegregated.")

53 percent of all nonwhite charter school students attend a school in the orange box. In other words, 53 percent of nonwhite charter students attend a school that is both highly segregated and more segregated than nearby traditional schools.

Below is a table with full data on racial sorting in charters. As can be seen, compared to traditional school students, charter students are typically more likely to be exposed to members of their own racial group and less likely to attend schools with a disproportionate share of other racial groups.

This is not the final word on charter segregation, of course. A city may be diverse overall but segregated internally; the traditional schools nearest a charter may be themselves segregated. In addition, although municipal boundaries permit for more convenient comparative analysis, district boundaries are often more relevant for students. The two do not always align: some cities are split between multiple districts, while other districts include multiple cities. We hope to address some of these issues in subsequent analyses.

Nonetheless, the data currently available strongly supports the idea that, compared to more traditional public schools, charters are contributing to increased school segregation.